The Clean Architecture Trap

We adopt patterns like Clean and Hexagonal Architecture to fight complexity, but often end up creating more of it. This post dives into why this happens and how a pragmatic approach focused on value and evolution can save your codebase from the "best practice" trap.

Clean, Hexagonal, and Onion architectures promise maintainable, scalable, and decoupled code. They are powerful patterns championed for their ability to isolate core business logic from external concerns. However, in my experience, I've seen many development teams adopt these patterns only to end up with a bloated, over-engineered codebase that's a nightmare to navigate.

Why does this happen? In this article, I'll explore the common pitfalls of applying these architectural patterns dogmatically and provide some pragmatic guidelines to help you design systems that are lean, effective, and evolve with your needs.

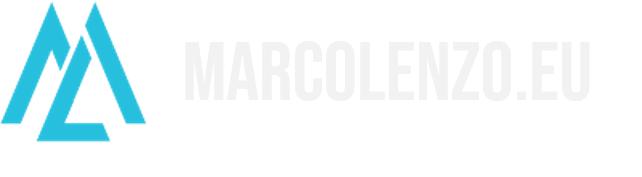

The Core Principle: The Dependency Rule

The central tenet of these architectures is the Dependency Rule, an application of the Dependency Inversion Principle. It states that our core business logic—the rules that make our application unique—should not depend on anything external.

This includes:

- The UI (Web, Mobile, CLI)

- Infrastructure (Databases, Message Brokers)

- Third-party libraries or frameworks

The goal is to have a core logic that is stable, decoupled, and easily testable, isolated from the whims of external technology choices. You should be able to swap your database from MySQL to MongoDB or change your web framework from Spring to Quarkus without rewriting your core business logic. That's the dream.

Where It All Goes Wrong

So, if the principle is so sound, where do teams go wrong? The risk lies in forgetting that these are guidelines, not dogmas. While these tenets provide excellent guidance, they are not a one-size-fits-all template. We must still apply our judgment and problem-solving skills to understand what our application truly needs.

Without this critical thinking process, the result is almost always an over-engineered system.

A Real-World Tale of Incidental Complexity

Let me tell you a story about a financial application I reviewed. The requirement was simple: a user inputs data into a form, presses a button, and the data is saved to a database. That's it. No complex business rules, no intricate workflow.

The team, aiming for best practices, decided to use Hexagonal Architecture. They started with a reasonable five-module structure: adapters for the web and database, and the core logic split between application and domain rules.

However, this structure quickly ballooned. To handle that simple form submission, the code evolved into at least 20 different classes and interfaces. Each module added its own set of objects (DTOs, Domain Objects, DBOs), services, and mappers. With the exception of the innermost business logic, every layer existed primarily to translate data for the next.

The real issue wasn't just the number of layers; it was that the layers themselves were empty. They contained no meaningful logic. They were just pass-throughs, existing only to satisfy an architectural rule on a diagram. This created a mountain of incidental complexity that added zero business value, made the code incredibly difficult to navigate, and turned simple changes into a multi-file-editing chore.

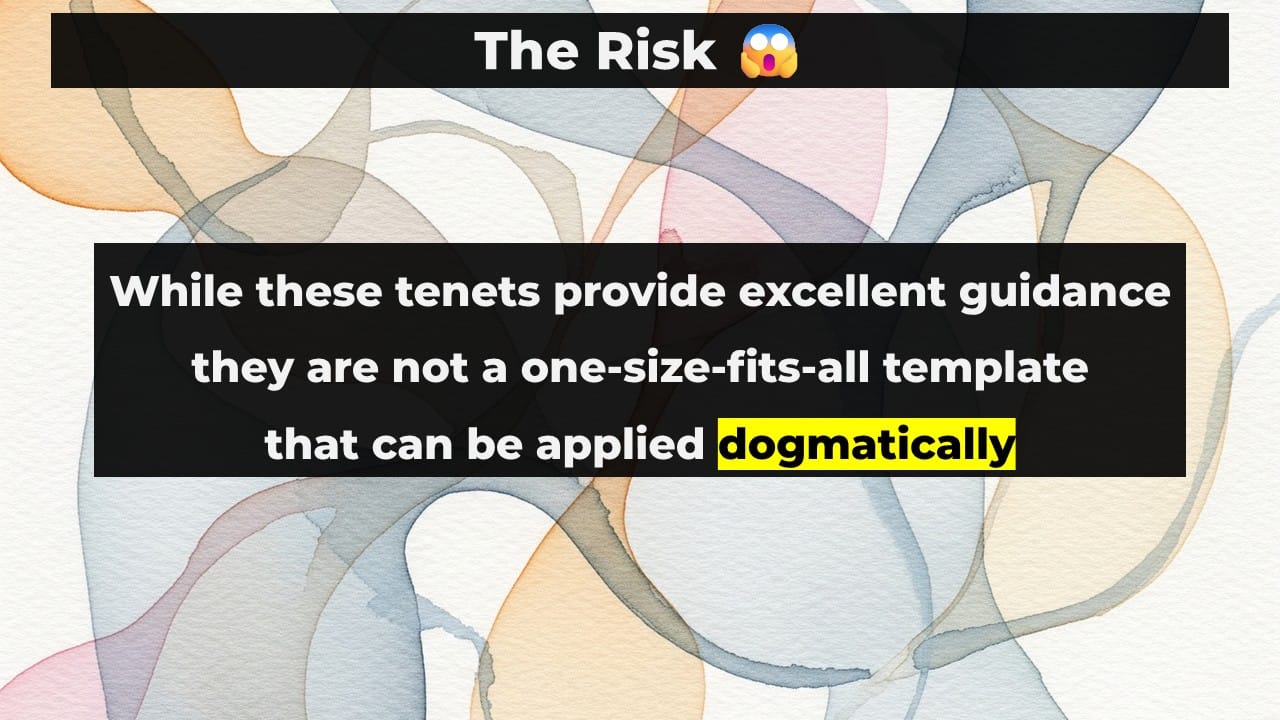

The Solution: A Pragmatic Mindset Shift

How do we avoid this trap? We need to change our mindset from architectural purism to pragmatic engineering.

1. Start with "Just Enough" Architecture

Begin with the simplest possible structure that solves the problem you have today, not the problem you anticipate tomorrow or in a year. Resist the urge to add layers for hypothetical future requirements. Remember, it's far easier to add a layer when you genuinely need it than to remove a useless one that's already tangled throughout your codebase.

2. Embrace Evolutionary Architecture

Your architecture isn't set in stone. Allow it to evolve. Let new layers and abstractions emerge organically as the application's complexity grows. This is Just-in-Time architecture, not Just-in-Case.

3. Treat Layers as an Investment

Every layer you add has a cost. It costs time to build and, more importantly, it costs time to maintain over the long term. Before adding a layer, ask yourself: is the return on this investment greater than its cost?

Here are some guidelines to evaluate that investment.

A layer is a good investment if it:

- ✅ Hides significant implementation details (especially from external clients).

- ✅ Enforces critical and complex business rules.

- ✅ Reduces cognitive load by creating a clear and helpful abstraction.

- ✅ Has high cohesion, meaning the classes within it collaborate closely to do one thing well.

A layer is a bad investment if it:

- ❌ Is just a pass-through with little to no logic.

- ❌ Adds navigational complexity without providing clarity.

- ❌ Leaks implementation details to its clients.

- ❌ Breaks the Dependency Rule (e.g., an inner layer depending on an outer one).

Putting Principles into Practice: A Product API

Let's apply this thinking to a simple Product API for saving and retrieving product details.

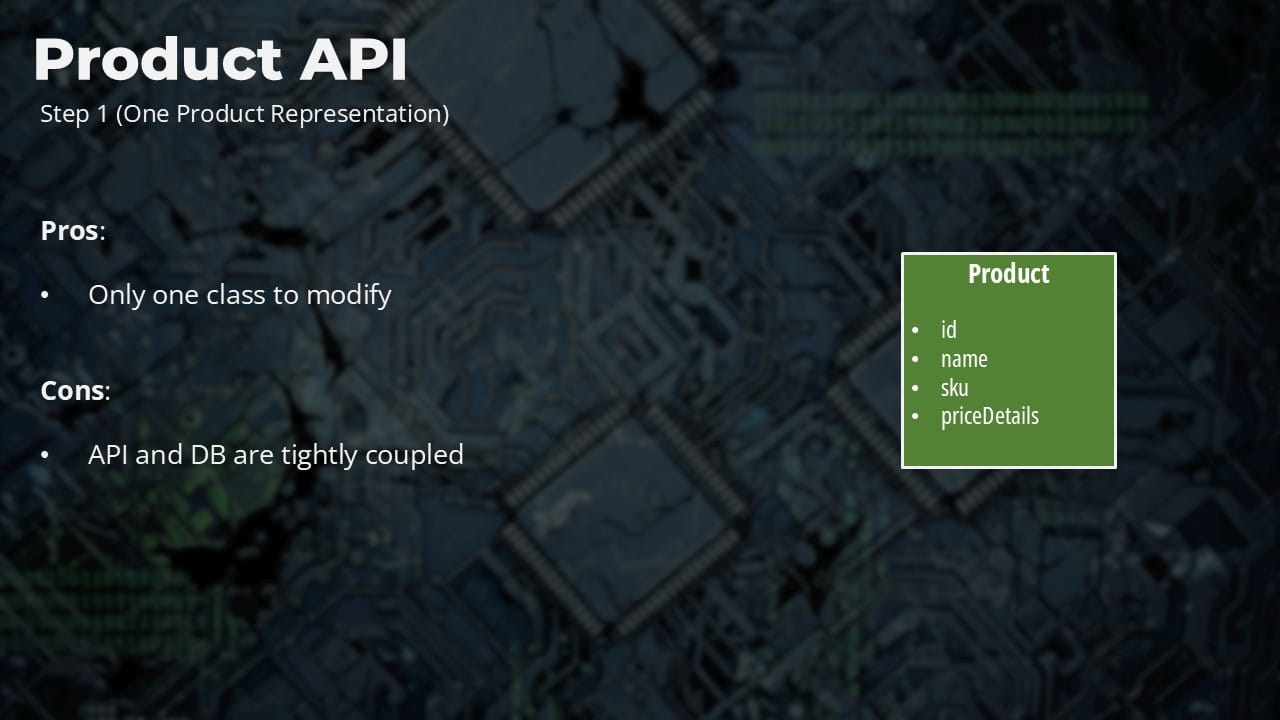

Step 1: The Simplest Thing That Could Possibly Work

The most straightforward design is a single Product class used for the API (DTO) and the database (Entity).

- Advantage: Extremely fast to develop. Changes (like adding a field) only require modifying one class.

- Disadvantage: The API contract and database schema are tightly coupled. A change in one forces a change in the other.

- When to use it: Perfect for solo projects, proof-of-concepts, startups moving at breakneck speed, or internal services where you control both the server and all its clients.

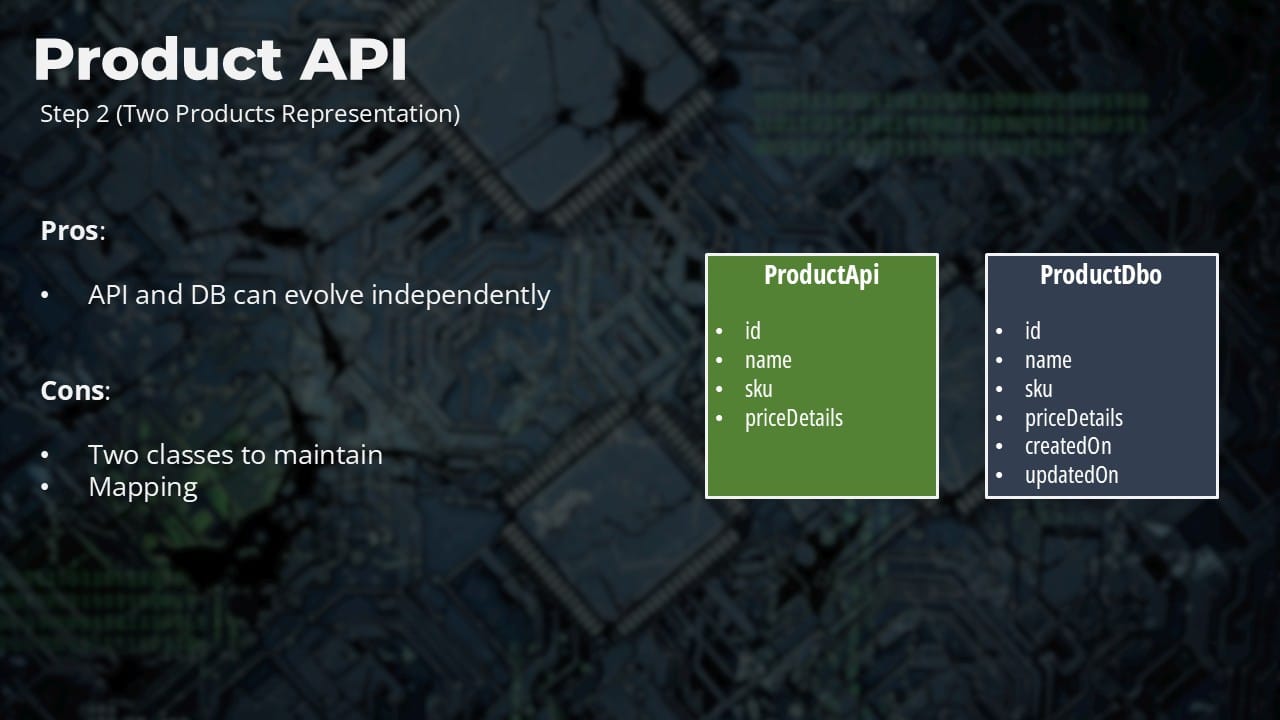

Step 2: Evolving to Add a Seam

As soon as external teams or customers start using your API, the tight coupling becomes a liability. Now is the time to evolve. We introduce a dedicated ProductApi class (DTO) and a ProductDbo class (Entity).

- Advantage: The API contract is now decoupled from the database schema. You can change them independently.

- Disadvantage: You now have two classes to maintain and must implement a mapping layer to translate between them.

- When to use it: This is the standard for most applications with external consumers. It provides a clean boundary and a stable API contract.

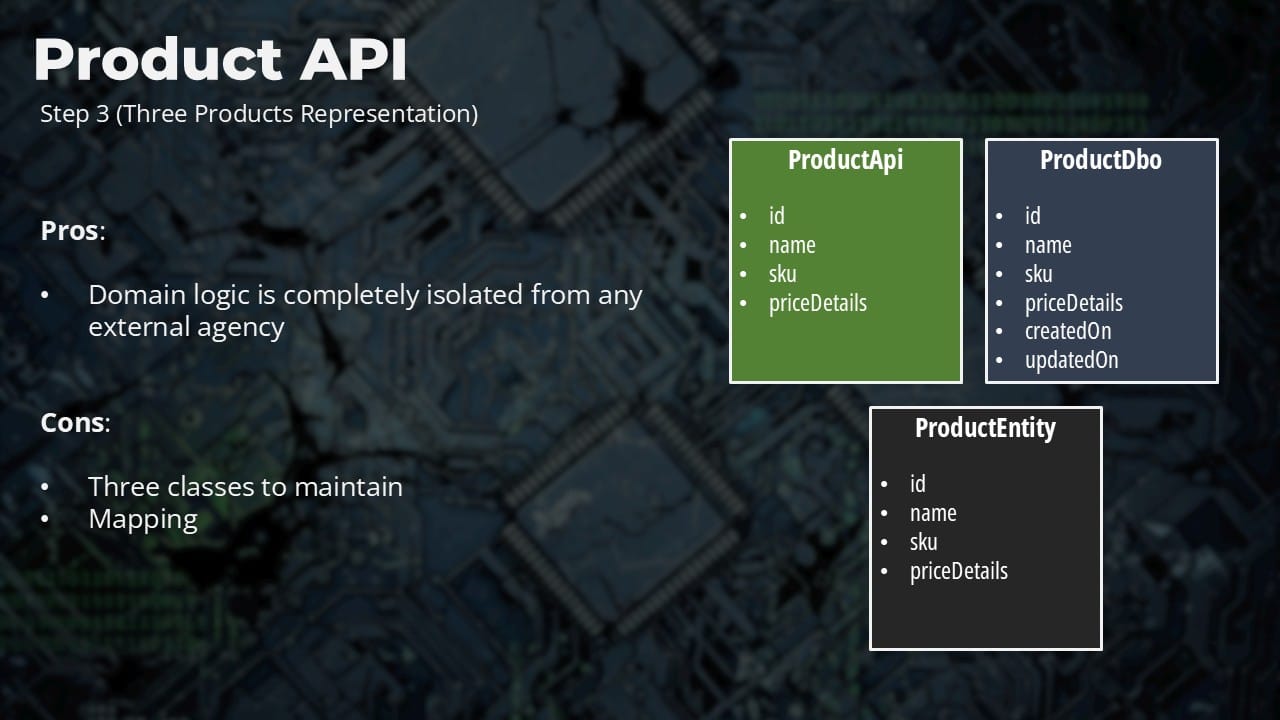

Step 3: The "Pure" Hexagonal Approach

A strict application of Clean Architecture would introduce a third Product object for the core domain layer, with no dependencies on any framework or infrastructure.

- Advantage: The core domain logic is completely decoupled.

- Disadvantage: You now have three classes and two layers of mapping, adding significant complexity for a simple CRUD operation.

Is this third step a good investment? If you have no complex business logic and no concrete plans to change your database or framework, in my opinion, it is not. The return on investment is negligible, and the cost in complexity is high. It's pure over-engineering.

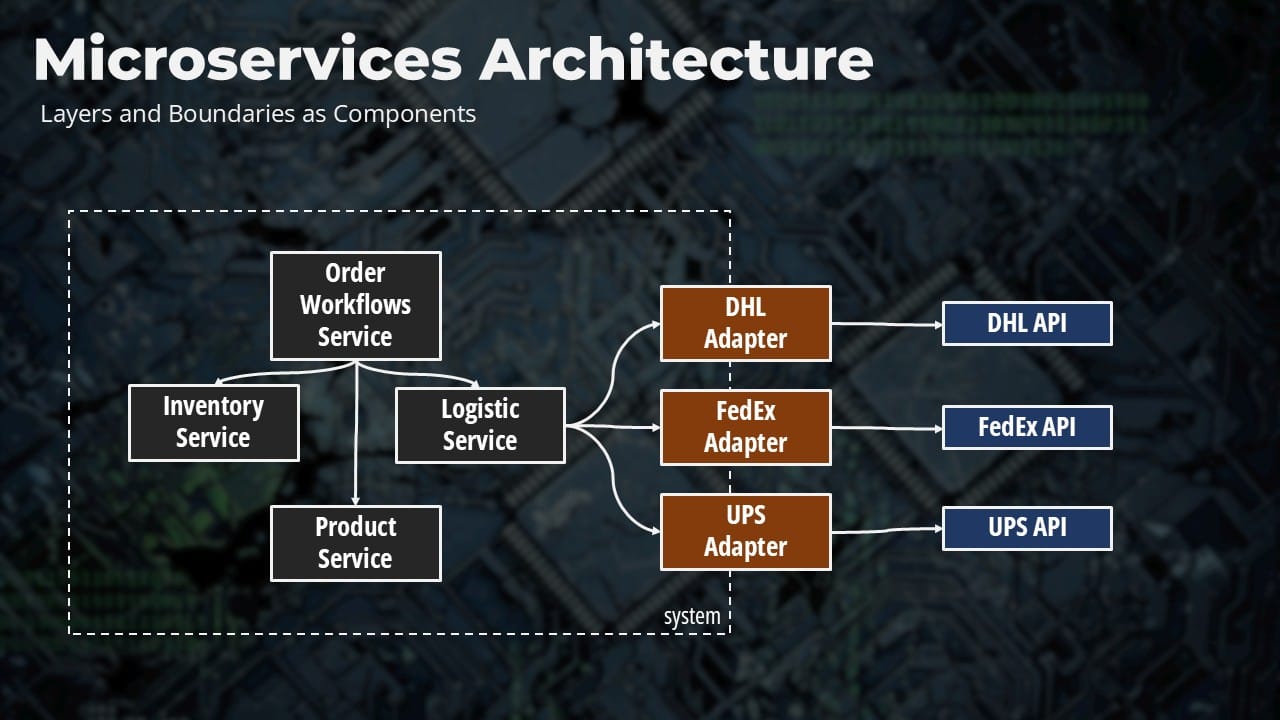

From Application to System-Level Thinking

These principles don't just apply within a single application; they apply to the system as a whole. If you're decomposing your system into microservices, remember that the services themselves are layers. They are a strong form of abstraction.

Don't make the mistake of recreating the complex, multi-layered packaging of a monolith inside each microservice. Keep your microservices as lean as possible.

For example, instead of an "adapter" package inside your service, you could have a dedicated Adapter Microservice. Imagine you need to integrate with multiple shipping carriers. You could have a core Logistics microservice and then separate adapter microservices for DHL, FedEx, and UPS. Each one handles the specific protocol and translation for that third party, keeping the core service clean.

Final Thoughts

Clean, Hexagonal, and Onion architectures are powerful tools, but like any tool, they can be misused. By shifting our perspective, we can leverage their strengths without falling into the trap of over-engineering.

- Challenge the Dogma: Architectural patterns are guidelines, not unbreakable laws. Always ask, "What value does this add right now?"

- Start Simple and Evolve: It's easier to add a necessary layer later than to remove a useless one.

- Treat Layers as an Investment: Every layer must provide more value than the complexity it introduces. If you can't clearly name the benefit, you probably don't need it.

Let's stop being architectural purists and start being pragmatic, effective engineers who build what's needed, when it's needed.